Thursday, September 10, 2009

Moving to China

I started a new blog for my China trip. It seems like the thing to do to have a dedicated trip blog, and I thought I'd see what all the fuss is about over at Wordpress. You can find me here. Wordpress, Blogger, and many other sites are currently blocked in China, and I had to subscribe to a VPN service to access them, so please don't use my real name in comments or links to the blog. Thanks for reading!

Saturday, June 27, 2009

Um

Well, what to write about now? I can't believe it took me seven months to finish "blogging" my China trip. Here's a highlights reel of what I missed blogging about while I was transcribing my travel journal entries (or, more properly, procrastinating on transcribing my journal entries):

I went to the Bay Area for a conference, visited some people, and went to a wedding. Obama got elected. I turned 29 and resolved to make a point of doing adventurous things in my last year as a 20-something. I dressed as an elf for Santarchy and threw myself a party. I went home for the holidays, spent some quality time with my grandmother's awesome cat, and decided to try to woo one of the tame backyard cats into living in the house, a project that proved more difficult than expected. I achieved Silver Preferred status on USAir, a privilege I have yet to take advantage of. Obama got inaugurated; I, G.R., and at least a million other people were there. K got accepted to a graduate program in global health and decided she wants to move to Virginia. A good friend from my Ithaca days moved to DC; several friends left. Many people I know got laid off; some got new jobs, and others decided that freelancing is the way to go. I started a vegetarian cooking club. Three co-workers had babies. My brother got engaged. I applied for many jobs, interviewed for a few, and was offered none. I got my first cavity. I started another summer Chinese class. Oh, and I decided to move to China.

That's right: just when you thought you might be able to read about something other than China in this space, I've decided that now is a good time to move to China. After nearly three years in DC I'm ready for a new adventure, and my experience in October showed me that if I'm highly unlikely to realize my longtime goal of becoming fluent in Mandarin if I stay here. No, I don't have a job there, and no, I don't want to move without one, so I'm thinking August is the earliest I'll be able to make this happen. But I'm about 95% sure at this point that I'm China-bound.

Oh, and if anyone knows someone in need of a sweet summer sublet in DC, send them my way.

I went to the Bay Area for a conference, visited some people, and went to a wedding. Obama got elected. I turned 29 and resolved to make a point of doing adventurous things in my last year as a 20-something. I dressed as an elf for Santarchy and threw myself a party. I went home for the holidays, spent some quality time with my grandmother's awesome cat, and decided to try to woo one of the tame backyard cats into living in the house, a project that proved more difficult than expected. I achieved Silver Preferred status on USAir, a privilege I have yet to take advantage of. Obama got inaugurated; I, G.R., and at least a million other people were there. K got accepted to a graduate program in global health and decided she wants to move to Virginia. A good friend from my Ithaca days moved to DC; several friends left. Many people I know got laid off; some got new jobs, and others decided that freelancing is the way to go. I started a vegetarian cooking club. Three co-workers had babies. My brother got engaged. I applied for many jobs, interviewed for a few, and was offered none. I got my first cavity. I started another summer Chinese class. Oh, and I decided to move to China.

That's right: just when you thought you might be able to read about something other than China in this space, I've decided that now is a good time to move to China. After nearly three years in DC I'm ready for a new adventure, and my experience in October showed me that if I'm highly unlikely to realize my longtime goal of becoming fluent in Mandarin if I stay here. No, I don't have a job there, and no, I don't want to move without one, so I'm thinking August is the earliest I'll be able to make this happen. But I'm about 95% sure at this point that I'm China-bound.

Oh, and if anyone knows someone in need of a sweet summer sublet in DC, send them my way.

Monday, May 25, 2009

Odyssey

[Written on October 5]

[Written on October 5]Arrived on the afternoon of the third, and have felt overwhelmed to some extent since my plane rolled up to the gate, The journey was about as comfortable as a 13-hour flight in coach can be; I think I'm a fan of Air Canada. The difficult part was getting up at 3:30 am to catch a plane to Toronto, only to wait in the airport for five hours.

I left the Beijing airport on an impressive high-speed train and transferred to the subway with no problems. I have only myself to blame for the series of unfortunate events that commenced once I got off the subway, since I had forgotten to print the confirmation email I received when I made my hostel reservation, or even to read it closely enough to realize that the hostel I thought I was reserving at no longer existed. Apparently the Beijing Gongti hostel had been kicked out of the Worker's Stadium and reincarnated as the Golden Pineapple Hostel somewhere nearby.

But I was not to learn this until I checked my email the next evening. At the time, I tried relying on Lonely Planet, signs near the Worker's Stadium (on these the hostel still existed), and asking people who worked around the stadium, not one of whom had ever heard of the place. Most of them were determined to help me, though, which led to much wasted time. one exceptionally kind woman, who spoke not a word of English, led me at my request to a shop to use the telephone. the phone was in use, so she took me to a second shop, where I tried calling the hostel--no answer. Then she discussed my predicament at length with other shop patrons. Then we went back to the stadium park, and I pointed out to her on the map at the gate where the hostel was supposed to be. I'm pretty sure she didn't understand this, just as I understood next to nothing she said, except when she commented that finding this hostel was really not easy. I agreed wholeheartedly.

Then she explained her plan, which I understood not at all, but it seemed easier to follow her than to try harder to extricate myself from her leadership. I'd tried to extricate myself already, thanking her when we arrived at the shop with the phone, and trying to explain afterward that I was just going to go back to the park and look some more, but to no avail.

The new plan took us out of the park, past restaurants that included an Outback Steakhouse, and far away. I felt increasingly desperate as we grew further from the stadium, with its signs that assured me the hostel was right there, but I was strangely resigned to my fate. The intense physical discomfort that came with wandering Beijing with a pack hardly had meaning anymore.

After 10 minutes or so we came to a sort of shopping center, where my guide looked at the list of businesses. Of course, the hostel wasn't on it. I'd been holding out hope that she was leading me to an alternative hostel, but this was clearly not the case. She asked an older couple walking by about the hostel, and everyone looked at the map in my Lonely Planet book for the umpteenth time that night. The old couple pointed out the obvious, which was that this hostel was by the stadium.

We started back. In an effort to avoid walking and regain some measure of control over my own destiny, I hailed a cab. I tried to offer my guide a lift, since presumably she was returning to the stadium grounds as well, but she probably didn't understand where I was going, and didn't get in. The driver didn't understand either, and dropped me off a few blocks later. But at least I'd saved a few blocks of walking.

I went back to the park and looked some more, until it truly seemed impossible that this hostel existed. Then I went to a hotel I'd seen while we were on our way to the shop with the phone. It cost more than twice what I'd have paid at the illusory hostel, but that was still only about $50. To say it was worth it would be an understatement.

My first Chinese lesson: Be careful whom you ask for help.

About the photograph: No, I did not open the 25 yuan package on my hotel nightstand to see how the vibrating condom worked. Anyone who knows is encouraged to comment (anonymously, if necessary).

Monday, May 18, 2009

Beijing: Day one

I woke up early--I'd slept in short spurts all night long--and set off in search of another Lonely Planet-recommended hostel in the neighborhood. This one seemed to have ceased to exist as well, but I'd seen signs for another hostel the night before, and this one I eventually found. I moved, then set out for the Forbidden City and Tiannanmen Square.

The square was still decorated for the Olympics--I enjoyed seeing the Olympic mascots miming various sports. Lines of soldiers marched purposefully here and there, and Mao's portrait beamed down benevolently on us all.

I worked my way into the Forbidden City eventually and was suitably impressed. Apart from the main courtyards, my favorite parts were the exhibits of various treasures, like the empress's hair pins.

My tired feet and the subway bore me back to a street near the hostel, where I had my first real meal in China, a tofu-vegetable dish from which I carefully removed the pork.

My hunger sated, I felt overwhelmingly sleepy and had to force myself to check email and read for a few hours before passing out at around 8:00.

The square was still decorated for the Olympics--I enjoyed seeing the Olympic mascots miming various sports. Lines of soldiers marched purposefully here and there, and Mao's portrait beamed down benevolently on us all.

I worked my way into the Forbidden City eventually and was suitably impressed. Apart from the main courtyards, my favorite parts were the exhibits of various treasures, like the empress's hair pins.

My tired feet and the subway bore me back to a street near the hostel, where I had my first real meal in China, a tofu-vegetable dish from which I carefully removed the pork.

My hunger sated, I felt overwhelmingly sleepy and had to force myself to check email and read for a few hours before passing out at around 8:00.

Saturday, April 11, 2009

Beijing: Day two

Went to the Lama Temple, where there were many people praying among clouds of incense. Was strangely underwhelmed until I wandered into an exhibit of sculptures of strange, Indian-looking gods.

Went to the Lama Temple, where there were many people praying among clouds of incense. Was strangely underwhelmed until I wandered into an exhibit of sculptures of strange, Indian-looking gods. It was raining a little. I walked around nearby hutongs for a bit, then down an important street past a Ming-era center of Confucian learning. I feasted at a somewhat pricey vegetarian buffet on the same street; though it was obviously geared toward tourists, I took comfort from the fact that most of the tourists were Chinese.

It had occurred to me while I was at the Lama Temple that I wasn't really in the traveling mindset yet. And why not? Maybe because I hadn't seen anything really surprising yet, with the possible exception of Beijing's sparkling subway system. I needed to find something weird. After lunch I set out to buy a ticket for a kung fu show, another wild goose chase I won't go into other than that I finally did find the Chaoyang Culture Center, it apparently no longer hosts kung fu shows. Clearly the Beijing described in my Lonely Planet--published in spring 2007--was not the Beijing of October 2008.

I caught a taxi to the Pearl Market next and tried out my haggling skills on a windbreaker. The experience taught me that my haggling skills needed work. I didn't stay at the Pearl Market for long--not weird enough, and it seemed sensible to leave the shopping to the end of my trip. So I crossed the pedestrian bridge and entered the park surrounding the Temple of Heavenly Peace.

There for the first time, I felt myself really getting in to the traveling groove. People were singing in a huge group; others were playing a game with ping pong paddles but no table; down a little further people were playing instruments; further still, there were women with red spangled scarves around their waists dancing to recorded music. In more secluded spots among the trees people stretched and practiced tai chi. It was lovely and strange.

I wandered the park until dark. A sign claimed that some of the cypresses in the park (the park where the emperors used to come to pray for big harvests) were 800 years old. Here's a country Americans tend to think of as recklessly destroying its environment, yet in the heart of Beijing it's harbored trees through several dynasties and foreign invasions, a civil war, Communism, the Cultural Revolution, capitalism, and the city's famously polluted air.

At dark I headed to the famous snack street, but skipped the fried bugs on sticks--the weirdest thing I ate was fried ice cream on toast. The area the snack market is in seems like Beijing's answer to Times Square. In fact many parts of Beijing--those that I saw, anyway--were bigger, newer, and cleaner than the nicest parts of American cities. After snack street I turned in early once again, but this time with good reason: My bus to the Great Wall was to leave at 6:30 am the next day.

Sunday, April 05, 2009

The wall

On October 6 I went to the Jinshanling section of the Great Wall with a bus bull of backpackers who'd booked the trip through our various hostels. It was a 3-hour drive each way to this less-trafficked section of the wall. We walked from there to the Simatai site, 10 km away. It was great to breathe fresh air again and see the wall, and it was a perfect sunny day. But it was another essentially unsurprising activity.

On October 6 I went to the Jinshanling section of the Great Wall with a bus bull of backpackers who'd booked the trip through our various hostels. It was a 3-hour drive each way to this less-trafficked section of the wall. We walked from there to the Simatai site, 10 km away. It was great to breathe fresh air again and see the wall, and it was a perfect sunny day. But it was another essentially unsurprising activity.Back in Beijing I collected my backpack from the hostel and headed to the train station. I'd booked a ticket through my hostel, and only "hard seat" class spots were still available--the hostel worker explained that this was because people were returning home after the October 1 holiday week. When I'd read about hard seat in books about China I'd pictured a bench, but these were actually lightly-padded seats with non-reclining backs. I fell asleep almost immediately, and slept for much of the 12-hour trip, but woke up with quite a sore neck.

Terra cotta warriors

It was foggy and rainy in Shaanxi province. I'd made a reservation for once, and got a shuttle from the station to the hostel. Feeling like a new woman after a shower and breakfast, I set out to buy my next train ticket and see the terra cotta warriors. I managed to use my Chinese to buy a "hard sleeper" ticket for the next day, and left the train station feeling quite proud of myself, even though I was to leave at 13:20 instead of in the evening, as I would have preferred.

It was foggy and rainy in Shaanxi province. I'd made a reservation for once, and got a shuttle from the station to the hostel. Feeling like a new woman after a shower and breakfast, I set out to buy my next train ticket and see the terra cotta warriors. I managed to use my Chinese to buy a "hard sleeper" ticket for the next day, and left the train station feeling quite proud of myself, even though I was to leave at 13:20 instead of in the evening, as I would have preferred.I walked in front of the train station looking for the shuttle bus to the warriors museum. There were huge puddles everywhere and I accidentally stepped in a few, wetting my feet through my sturdy hiking shoes. But I didn't wander long before a bus conductor saw me and pointed out the bus to me. I'd ridden a taxi to the train station and bough a ticket in Chinese, then found the correct bus, all in 20 minutes or so--my confidence in my travel skills was beginning to return.

I'd seen the warriors museum on the Travel Channel just a few months before, so it seemed an unlikely candidate for a site that would surprise me. But I found the warriors' expressive faces and broken, jumbled bodies (in the partly-excavated sections) strangely moving, as if they were real people who'd been interred here alive. In fact they do represent the exquisite life's work of countless nameless artisans, buried pointlessly for milennia thanks to an emperor's delusion of immortality.

After a few hours with the warriors I took the bus back to the city. It was about 6:00 when I arrived, and cold. I was very hungry. I walked down a major street for awhile without seeing anything remotely appealing, then spotted a restaurant on a side street. It didn't look like the kind of place that got many waiguoren, but I went in anyway.

One of the waitresses opened the door for me and asked how many people I was. This seems to be a mandatory question at restaurants in China, even when, as then, there's no one else around. I don't know whether it's an immutable rule that it must be asked, or if people are simply incredulous that anyone would go to a restaurant alone.

My apprehensions were confirmed when I got the menu: It had no English, no pinyin, and no pictures. The waitress patiently awaited my order as I whipped out my tiny dictionary, but clearly nether it nor I were up to the task of decoding that enormous menu. I decided to throw myself on the mercy of the waitress, even though she hadn't understood me the first time I asked for tea.

In Chinese, I explained that I don't eat meat, that I like vegetables and tofu and mushrooms. She aksed whether I liked spicy food, and I said no. There were other questions that I tried to guess at and muddle through. I said yes to rice.

And voila! A dish of tofu, mushrooms, onions, and peppers appeared a few minutes later, sans meat, with rice. I was incredibly awkward in Chinese, but maybe I could get by after all, I thought.

I turned in early again. This time my excuse was that I'd been on a train the night before. Besides, if I was to leave at midday, I wanted to get an early start.

Xi'an

I got a reasonably early start on the 8th, though I was slowed by some difficulty finding breakfast. I was determined not to eat in my hostel, on the grounds that it was overpriced, smokey, and too backpacker-y. But the coffee shop I found wasn't open yet, and street food just wasn't as ubiquitous as I'd expected. So... I settled for toast and scrambled eggs in the hostel next door, which turned out to be much prettier than mine. At least my quest led me through a strip of park that runs along the outside of the city wall, where early risers were socializing and exercising.

After breakfast I ascended the city wall at the South Gate and rented a rickety bike, then jounced in a rectangle around the central part of town. It's an impressive wall in terms of size, condition, and pretty sentry buildings and watch towers, but once you've seen one strip of it, you've seen it all. It was interesting to get a look at the slums, since I'd only seen the nicer parts of Xi'an to that point.

I used all 100 minutes of my bike rental to get all the way around (it was a long wall, and a rickety bike), then got a taxi to the town's big, ancient mosque. It was a very Chinese-looking mosque complex, and though it looked to be in good condition it had a dusty patina, which I liked. I was disappointed that only worshipers were allowed in the prayer hall, though I understood it.

Short on time, I stopped at several tiny shops in the Muslim quarter for provisions: several pieces of bread, some unidentified fruit, a preserved egg, pastries. I got a taxi back to the hostel, collected my backpack, and took a taxi to the train station.

Yes, I took a lot of taxis in China. It's lazy, but it's hard to justify trying to brave the bus system when someone will drive me where I want to go for a little over a dollar. I am on vacation. But taxis don't solve every problem: The drivers don't speak English, have never heard of my hostel, and didn't understand it I try to tell them the address. A Lonely Planet map (with street names in pinyin and characters) means nothing to them. So I coped by telling them a landmark near where I want to go, then walking. Eventually I started painstakingly copying addresses from Lonely Planet onto a small piece of paper, which they seemed to understand better than my spoken Chinese.

The 16-hour train ride was uneventful and fairly comfortable, with one scenic mountainous stretch before it got dark. I think there was meat in one of the pastries I'd bought, but the others were good. The dried fruit turned out to be crabapples, I thought--I couldn't remember ever having eaten a crabapple, so I couldn't be sure. The preserved egg tasted ok, but looked black and gelatinous and had a chemical smell. When I got to the yolk it was slimy, and I actually gagged. I threw the rest away.

I woke up sometime after 4:00 am and found the other three passengers from my compartment gone. I worried that I'd missed Chengdu, and stayed awake to make sure I wouldn't, if I hadn't already. In fact the conductor would have woken me up; she'd collected my ticket earlier, carefully folded it three ways, and pu7t it in a pocket in a book, handing me a plastic rectangle with my car and compartment numbers. This ritual was repeated in reverse shortly before arrival.

After breakfast I ascended the city wall at the South Gate and rented a rickety bike, then jounced in a rectangle around the central part of town. It's an impressive wall in terms of size, condition, and pretty sentry buildings and watch towers, but once you've seen one strip of it, you've seen it all. It was interesting to get a look at the slums, since I'd only seen the nicer parts of Xi'an to that point.

I used all 100 minutes of my bike rental to get all the way around (it was a long wall, and a rickety bike), then got a taxi to the town's big, ancient mosque. It was a very Chinese-looking mosque complex, and though it looked to be in good condition it had a dusty patina, which I liked. I was disappointed that only worshipers were allowed in the prayer hall, though I understood it.

Short on time, I stopped at several tiny shops in the Muslim quarter for provisions: several pieces of bread, some unidentified fruit, a preserved egg, pastries. I got a taxi back to the hostel, collected my backpack, and took a taxi to the train station.

Yes, I took a lot of taxis in China. It's lazy, but it's hard to justify trying to brave the bus system when someone will drive me where I want to go for a little over a dollar. I am on vacation. But taxis don't solve every problem: The drivers don't speak English, have never heard of my hostel, and didn't understand it I try to tell them the address. A Lonely Planet map (with street names in pinyin and characters) means nothing to them. So I coped by telling them a landmark near where I want to go, then walking. Eventually I started painstakingly copying addresses from Lonely Planet onto a small piece of paper, which they seemed to understand better than my spoken Chinese.

The 16-hour train ride was uneventful and fairly comfortable, with one scenic mountainous stretch before it got dark. I think there was meat in one of the pastries I'd bought, but the others were good. The dried fruit turned out to be crabapples, I thought--I couldn't remember ever having eaten a crabapple, so I couldn't be sure. The preserved egg tasted ok, but looked black and gelatinous and had a chemical smell. When I got to the yolk it was slimy, and I actually gagged. I threw the rest away.

I woke up sometime after 4:00 am and found the other three passengers from my compartment gone. I worried that I'd missed Chengdu, and stayed awake to make sure I wouldn't, if I hadn't already. In fact the conductor would have woken me up; she'd collected my ticket earlier, carefully folded it three ways, and pu7t it in a pocket in a book, handing me a plastic rectangle with my car and compartment numbers. This ritual was repeated in reverse shortly before arrival.

Sunday, March 15, 2009

Chengdu by bike

The train pulled into Chengdu at 5:30 am. At the taxi stand I was besieged with offers of a ride, but didn't realize the touts weren't official taxi drivers, but freelancers. One told me he'd take me to the Wenshu Temple (which was supposed to be near my hostel) for Y40, which I knew was ridiculous. I settled on Y15 with another, only to discover that his "taxi" was a motorcycle. No way was I getting on a motorbike at 5:30 am in a strange city, particularly not with my pack. I got to the temple in a real taxi for Y10.

I found the hostel with no problem, but there found my punishment for changing my lodging plans while on the train (choking on fumes, I'd decided it was critical to find a nonsmoker-friendly establishment). A sign informed me that the hostel had relocated, but notes were thoughtfully provided to direct taxi drivers to the new place. Sticking to the path of least resistance, I took a taxi to the new place. This turned out to be a good choice: Sim's Cozy Guesthouse is an oasis, cheap but comfortable and clean, with all the services a weary budget traveller could ask for.

I showered, breakfasted, and bought a plane ticket to Lijiang to leave Sunday evening. I bought a map and rented a bike and went back to the Wenshu Temple, which I explored thoroughly before feasting in its vegetarian restaurant. Then I walked along the streets in front of the temple, which are picturesque and touristy.

An old man with a smooth, friendly face and a cowboy hat stopped me on the sidewalk and asked where I was from. He told me he would give me an American history lesson. His strong accent and many missing teeth made it a hard lesson to understand, but the gist was that in 1943 Roosevelt sent airmen to Chengdu to fight the Japanese. People walking by turned to look at us curiously. The old man asked me where I was going in China, and made a comment about Xi'an that I didn't understand. Then he said goodbye.

I pedaled south to the giant Mao statue and admired the new subway station in the square in front of him. The next stop was the thatched cottage of Du Fu, a Tang dynasty poet. His actual cottage is long gone, but hundreds of years ago an admirer built a new cottage in the same area, and subsequent dynasties have maintained and added to the cottage. Not a bad way to venerate someone, I suppose.

This was clearly a major tourist attraction, and I was impressed that the Chinese had so much love for their poets. The only equivalent I could think of in the Anglophone world is Stratford-on-Avon. I resolved to read some of Du Fu's work back in the States.

I stopped in at the site's tea garden and was reading when a man came by my table and asked whether I was English. American was good enough--"you speak English, anyway." He was an overweight man in his 50s with a Chinese woman. She was well-dressed with fashionable glasses, perhaps 20 years younger than him. He asked me whether this was my first time in China and what I thought of it, and I said it was great but overwhelming, which was the prelude he needed to launch into a near-monologue about how China is better than England because it's cheaper and the people are friendlier and the women are "superior" to English women, because they won't argue with you. Also Chinese is the hardest language for English speakers to learn, but when he gets back to England he's going to put "her" into an English class, because it's much easier for a Chinese woman to speak English. "They're quite clever, you know. They're not as stupid as we think." I wondered whether my nodding could be taken as agreement that I thought the Chinese were stupid, or that they actually were clever. When he talked about liking women who won't argue I did say something like, "If that's what you're into," but I'm not one to pick fights with strangers in tea houses.

I watched him waddle off with his mail-order bride, or whatever she was, after they'd showed me their electronic translators (his black, hers pink and white), and marveled that anyone could be so obliviously offensive. But his colonial outlook seemed so anachronistic in the China I saw that I couldn't get worked up about it, but somewhat grossed out.

I headed back toward the hostel post-tea, but managed to get a little lost. I think it took about an hour and a half to get there. Given my now-vast experience with bicycling in China, I will here record some principles:

Another early night. China overstimulated me with sensory information and with the depth of my own non-understanding. It also overwhelmed me with people, which might be why I became so introverted there. That day I was also having doubts about what I was accomplishing by traveling, doubts I'd had before. Since I can only hope to gain the most superficial understanding of a culture by wandering through a country for a bit, unable to speak the language, what's the point? I might as well be going around on a tour bus collecting pictures of myself with the Great Wall and the Tower of Pisa, or better yet, home watching the Travel Channel.

Yet the world still beckons. A superficial first-hand understanding seems superior to mere research.

I found the hostel with no problem, but there found my punishment for changing my lodging plans while on the train (choking on fumes, I'd decided it was critical to find a nonsmoker-friendly establishment). A sign informed me that the hostel had relocated, but notes were thoughtfully provided to direct taxi drivers to the new place. Sticking to the path of least resistance, I took a taxi to the new place. This turned out to be a good choice: Sim's Cozy Guesthouse is an oasis, cheap but comfortable and clean, with all the services a weary budget traveller could ask for.

I showered, breakfasted, and bought a plane ticket to Lijiang to leave Sunday evening. I bought a map and rented a bike and went back to the Wenshu Temple, which I explored thoroughly before feasting in its vegetarian restaurant. Then I walked along the streets in front of the temple, which are picturesque and touristy.

An old man with a smooth, friendly face and a cowboy hat stopped me on the sidewalk and asked where I was from. He told me he would give me an American history lesson. His strong accent and many missing teeth made it a hard lesson to understand, but the gist was that in 1943 Roosevelt sent airmen to Chengdu to fight the Japanese. People walking by turned to look at us curiously. The old man asked me where I was going in China, and made a comment about Xi'an that I didn't understand. Then he said goodbye.

I pedaled south to the giant Mao statue and admired the new subway station in the square in front of him. The next stop was the thatched cottage of Du Fu, a Tang dynasty poet. His actual cottage is long gone, but hundreds of years ago an admirer built a new cottage in the same area, and subsequent dynasties have maintained and added to the cottage. Not a bad way to venerate someone, I suppose.

This was clearly a major tourist attraction, and I was impressed that the Chinese had so much love for their poets. The only equivalent I could think of in the Anglophone world is Stratford-on-Avon. I resolved to read some of Du Fu's work back in the States.

I stopped in at the site's tea garden and was reading when a man came by my table and asked whether I was English. American was good enough--"you speak English, anyway." He was an overweight man in his 50s with a Chinese woman. She was well-dressed with fashionable glasses, perhaps 20 years younger than him. He asked me whether this was my first time in China and what I thought of it, and I said it was great but overwhelming, which was the prelude he needed to launch into a near-monologue about how China is better than England because it's cheaper and the people are friendlier and the women are "superior" to English women, because they won't argue with you. Also Chinese is the hardest language for English speakers to learn, but when he gets back to England he's going to put "her" into an English class, because it's much easier for a Chinese woman to speak English. "They're quite clever, you know. They're not as stupid as we think." I wondered whether my nodding could be taken as agreement that I thought the Chinese were stupid, or that they actually were clever. When he talked about liking women who won't argue I did say something like, "If that's what you're into," but I'm not one to pick fights with strangers in tea houses.

I watched him waddle off with his mail-order bride, or whatever she was, after they'd showed me their electronic translators (his black, hers pink and white), and marveled that anyone could be so obliviously offensive. But his colonial outlook seemed so anachronistic in the China I saw that I couldn't get worked up about it, but somewhat grossed out.

I headed back toward the hostel post-tea, but managed to get a little lost. I think it took about an hour and a half to get there. Given my now-vast experience with bicycling in China, I will here record some principles:

- Adopt an unshakable Zen mindset. Take nothing personally, and let nothing startle you.

- American ideas about right-of-way mean nothing. Pay attention to red and green lights, but treat them as suggestions.

- If you see an opening, take it.

- If you and another person go for the same opening, the one in the smaller vehicle yields. Bikes yield to everything but pedestrians.

- Keep in mind that there's safety in numbers. Do as the other bikes do.

Another early night. China overstimulated me with sensory information and with the depth of my own non-understanding. It also overwhelmed me with people, which might be why I became so introverted there. That day I was also having doubts about what I was accomplishing by traveling, doubts I'd had before. Since I can only hope to gain the most superficial understanding of a culture by wandering through a country for a bit, unable to speak the language, what's the point? I might as well be going around on a tour bus collecting pictures of myself with the Great Wall and the Tower of Pisa, or better yet, home watching the Travel Channel.

Yet the world still beckons. A superficial first-hand understanding seems superior to mere research.

Sanxingdui

From Chengdu I took a day trip to Sanxingdui, a site perhaps an hour away via two fuses. It's two museum buildings on the site of a 20-year-old archaeological dig. There's a very impressing collection of pottery, jade, and bronze artifacts that are like nothing that's been unearthed anywhere else, as far as I could glean from the exhibits. I spent a few hours there, fascinated.

Back at the Chengdu bus station I headed for a nearby monastery to try to get a late lunch at its vegetarian restaurant, which Lonely Planet claimed was open until 3:30. I arrived at 3:15 to find it shuttered. I was famished but took a walk around the monastery anyway (it's called Zhaojue). Nice place, but all the monasteries were beginning to look much alike by now. This one was distinguished by an ugly concrete pond full of small turtles. I'd never seen a higher concentration of turtles outside of a Dr. Seuss book.

Two giggling girls, perhaps 13 years old, ran to to me and asked a question, holding up a camera. I nodded, assuming they wanted me to take their picture, but of course they wouldn't have chased down the one foreigner in the place for that. The excitedly took turns taking one another's picture with me. Then they were off, with a chorus, of "xiexie, sank you!"

I wasn't sure what to make of this, but the girls were too cute and enthusiastic for me to regret having said yes. I said yes to all future picture requests, so I'm probably immortalized on Chinese Facebook pages as the giant, freckled foreigner with the crooked smile.

Famished, I walked back to the bus station, determined to catch a city bus back to the hostel. But after going to the trouble oflocating the buses, and then the right bus, I discovered that the smallest bill I had was Y50, which I was sure wouldn't fly for a Y1 fare. So I went to the taxi stand. The first taxi I got in rear-ended another car on the way out of the lot. I got out which the driver was talking to the inhabitants of the other car and got into a different taxi. I'm pretty sure that's where I lost my fleece, in the back seat of the unfortunate cab. I liked that fleece. All because I didn't have Y1.

I ate an enormous amount of ostensibly Sichuanese food in the restaurant of Sim's hostel, laid down for a bit, and then went to see a Sichuan opera. It was touristy by excellent, with music and puppeteering and flamboyant costumes and face-changing and fire-spitting. I'd been particularly interested in seeing the acrobatics, which were not what I expected: A pretty young woman laid on her back with her feet in the air and deftly turned and tossed first a pot, then a table, with her feet.

Back at the hostel I turned on CCTV International, China's state-run English station, as I got ready for bed. I'd become somewhat addicted to CCTV, partly for comforting background noise but mostly for its window into the government's perspectives and preoccupations. The brief roundup of the day's new reported that Obama was ahead of McCain by 11 points, which made my jaw drop. It wasthe first election news I'd heard since arriving.

Back at the Chengdu bus station I headed for a nearby monastery to try to get a late lunch at its vegetarian restaurant, which Lonely Planet claimed was open until 3:30. I arrived at 3:15 to find it shuttered. I was famished but took a walk around the monastery anyway (it's called Zhaojue). Nice place, but all the monasteries were beginning to look much alike by now. This one was distinguished by an ugly concrete pond full of small turtles. I'd never seen a higher concentration of turtles outside of a Dr. Seuss book.

Two giggling girls, perhaps 13 years old, ran to to me and asked a question, holding up a camera. I nodded, assuming they wanted me to take their picture, but of course they wouldn't have chased down the one foreigner in the place for that. The excitedly took turns taking one another's picture with me. Then they were off, with a chorus, of "xiexie, sank you!"

I wasn't sure what to make of this, but the girls were too cute and enthusiastic for me to regret having said yes. I said yes to all future picture requests, so I'm probably immortalized on Chinese Facebook pages as the giant, freckled foreigner with the crooked smile.

Famished, I walked back to the bus station, determined to catch a city bus back to the hostel. But after going to the trouble oflocating the buses, and then the right bus, I discovered that the smallest bill I had was Y50, which I was sure wouldn't fly for a Y1 fare. So I went to the taxi stand. The first taxi I got in rear-ended another car on the way out of the lot. I got out which the driver was talking to the inhabitants of the other car and got into a different taxi. I'm pretty sure that's where I lost my fleece, in the back seat of the unfortunate cab. I liked that fleece. All because I didn't have Y1.

I ate an enormous amount of ostensibly Sichuanese food in the restaurant of Sim's hostel, laid down for a bit, and then went to see a Sichuan opera. It was touristy by excellent, with music and puppeteering and flamboyant costumes and face-changing and fire-spitting. I'd been particularly interested in seeing the acrobatics, which were not what I expected: A pretty young woman laid on her back with her feet in the air and deftly turned and tossed first a pot, then a table, with her feet.

Back at the hostel I turned on CCTV International, China's state-run English station, as I got ready for bed. I'd become somewhat addicted to CCTV, partly for comforting background noise but mostly for its window into the government's perspectives and preoccupations. The brief roundup of the day's new reported that Obama was ahead of McCain by 11 points, which made my jaw drop. It wasthe first election news I'd heard since arriving.

Thursday, February 26, 2009

Big Buddha

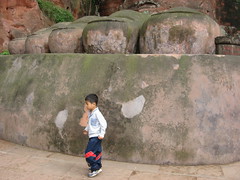

I took the bus two hours from Chengdu to Leshan to see the giant Buddha. It's supposed to be the biggest Buddha in the world, or even, according to something I saw, the biggest stone carving.

The place was swarming with tourists, mostly Chinese tour groups who mobbed the area to the side of Buddha's face to take pictures. There were other things to see on the top of the mountain, like a tall pagoda and yet another temple. I was hungry and bought a little 5 yuan bowl of noodles. It was hot enough that my eyes watered profusely and the noodle-stand women laughed gently at me. Several people asked to take pictures with me while I was there; there were only a handful of other Westerners.

The Buddha was big. No surprises there, but I'm glad I saw it.

As I left the site a man asked whether I was going to Chengdu and hustled me onto a minibus that would meet the big bus along the road. I was happy to be saved the effort of getting to the bus station. While we waited for the big bus the middle-aged Chinese couple who were the only other minibus passengers tried to talk to me. The woman spoke a little English. They said America was a nice country, and I said China was very interesting. Later, after the bus made a stop at a gas station with a fruit stand, the woman gave me an orange.

The bus left us at a station on the far outskirts of town, not the same one I'd left from. I couldn't figure out where I was or even how to take a taxi--none of the drivers were in their cars, although one woman told me she'd take me where I wanted to go (I'd written down the address of a restaurant) for 30 yuan, which sounded like far too much. Finally I got a cab driver who would turn on his meter; it cost 20 yuan, but the restaurant Lonely Planet had recommended so highly seemed no longer to exist. The person who invents a combination pocket translator and deliverer of travel information that's actually up-to-date will deserve to be very rich.

I saw a few Western restaurants and even an Indian place, but was determined to get some good Chinese food. I stopped into a place that looked fairly upscale, but I'd miscalculated: The menu wasn't in English, and there weren't really any vegetarian dishes. The first woman who tried to wait on me gave up in frustration. Then a young guy tried, and I randomly pointed to one of the dishes he said was a vegetable dish. It turned out to be a plate of broccoli--excellent broccoli, and served with rice, but not nearly enough for my empty stomach. Defeated, and feeling like one of the characters in Lost in Translation, I crossed the street and entered the Shamrock Pub.

At least half of the patrons were foreigners, and normally when traveling I become more gregarious. But even there I didn't talk to anyone except the waiter, just ordered an excellent "mocktail" and a flavorless vegetarian pizza, read, scribbled in my journal, and left before the live music started. If I kept up my antisocial ways, I thought, the nonstop schmoozing of the conference I'd soon attend in California would be quite a shock to my system.

The place was swarming with tourists, mostly Chinese tour groups who mobbed the area to the side of Buddha's face to take pictures. There were other things to see on the top of the mountain, like a tall pagoda and yet another temple. I was hungry and bought a little 5 yuan bowl of noodles. It was hot enough that my eyes watered profusely and the noodle-stand women laughed gently at me. Several people asked to take pictures with me while I was there; there were only a handful of other Westerners.

The Buddha was big. No surprises there, but I'm glad I saw it.

As I left the site a man asked whether I was going to Chengdu and hustled me onto a minibus that would meet the big bus along the road. I was happy to be saved the effort of getting to the bus station. While we waited for the big bus the middle-aged Chinese couple who were the only other minibus passengers tried to talk to me. The woman spoke a little English. They said America was a nice country, and I said China was very interesting. Later, after the bus made a stop at a gas station with a fruit stand, the woman gave me an orange.

The bus left us at a station on the far outskirts of town, not the same one I'd left from. I couldn't figure out where I was or even how to take a taxi--none of the drivers were in their cars, although one woman told me she'd take me where I wanted to go (I'd written down the address of a restaurant) for 30 yuan, which sounded like far too much. Finally I got a cab driver who would turn on his meter; it cost 20 yuan, but the restaurant Lonely Planet had recommended so highly seemed no longer to exist. The person who invents a combination pocket translator and deliverer of travel information that's actually up-to-date will deserve to be very rich.

I saw a few Western restaurants and even an Indian place, but was determined to get some good Chinese food. I stopped into a place that looked fairly upscale, but I'd miscalculated: The menu wasn't in English, and there weren't really any vegetarian dishes. The first woman who tried to wait on me gave up in frustration. Then a young guy tried, and I randomly pointed to one of the dishes he said was a vegetable dish. It turned out to be a plate of broccoli--excellent broccoli, and served with rice, but not nearly enough for my empty stomach. Defeated, and feeling like one of the characters in Lost in Translation, I crossed the street and entered the Shamrock Pub.

At least half of the patrons were foreigners, and normally when traveling I become more gregarious. But even there I didn't talk to anyone except the waiter, just ordered an excellent "mocktail" and a flavorless vegetarian pizza, read, scribbled in my journal, and left before the live music started. If I kept up my antisocial ways, I thought, the nonstop schmoozing of the conference I'd soon attend in California would be quite a shock to my system.

Sunday, February 22, 2009

A day at the park

On Sunday I resolved to do nothing in particular. I had a leisurely breakfast of fruit in my room and packed to the sound of CCTV. I called my great-aunt Lily, a task I'd neglected to take care of before coming to China. Lilly lives in San Jose, and I was planning to stay with her in a couple of weeks. I thought I should give her a heads-up. Hers was the first familiar voice I'd heard since leaving the States.

Next I called the cell phone for the Wenhai Ecolodge, a place I'd found a few months before when I Googled "Yunnan ecotourism." Going to an ecolodge in the jungle had been the highlight of my time in Peru, and I hoped there were similar opportunities in China. I'd made an email reservation with someone who seemed to speak English quite well, and now needed to work out how to get to the lodge. My options were hiking, horseback, or Jeep; I chose horseback. My pack was nice enough for jaunts around towns in search of hostels, but I'd never hiked with it, nor did I want to try. And having someone drive me up a mountain in a Jeep didn't seem very eco-friendly.

After taking care of a few other things I rented a bike and rode to what seemed to be Chengdu's main tourist shopping drag, a place with nice dark wood buildings. It adjoined a park where I went wandering, and confirmed my impression that going to the park is one of the best things to do in China. I saw an old man painting calligraphy on the paving stones with water and a giant brush. This in addition to the usual newspaper-reading, tea-drinking, and music-making.

I did have a destination in mind in the park, namely the Green Ram Taoist temple and its vegetarian restaurant. It's interesting how similar the Buddhist and Taoist temples look to my untrained eye. The main differences I picked out are the ubiquity of the yin/yang symbol (only Taoist), and the way the monks dress.

At the temples, I've seen monks chanting and people reverently lighting incense. I've also seen monks chatting on cell phones and hawking loogies, and woman kneeling to pray in a pink velour tracksuit with "Juicy" printed across her ass. It would be nice to get a tour of a temple sometime from someone knowledgeable, but until that happens, I'm not keen on going to more temples anytime soon.

At the restaurant, the waitress put a menu in front of me that looked like it might have been a relic of the Tang dynasty, if they'd had typewriters in the Tang dynasty. The edges of the pages were ragged. But I noticed later that the other patrons had nice menus with hard covers and laminated pages, and figured the waitress had given me the antique version because it was bilingual.

I was grateful for this, but it didn't completely solve my communication difficulties. When I pointed to a dish described as "pumpkin," the waitress tried to explain why I might not in fact want it, but I didn't understand. So she helpfully went and got the vegetable in question and showed it to me. I looked like an extremely warty cucumber. I nodded--I was in China to try new things, right?--but it turned out to be the most bitter vegetable I'd ever tasted. Fortunately I'd also ordered a tofu dish. I was beginning to catch on that even if you're a lone diner, and you know that Chinese portions are huge, you don't order just one thing at a Chinese restaurant.

Afterward I found my bike--this took a little time--and went to the People's Park in the heart of the city. This one has kiddie rides, full bands giving free concerts, and a garden of Bonsai trees. It also has a famous teahouse that I wanted to try. The teahouse is huge and sprawling, set on a small lake where families rent paddle boats. Men walk around tinging their ear-cleaning instruments (a sound much like a triangle) to advertise their services. I finally agreed to a 20-minute massage from one.

He focussed mostly on my arms, gripping them so tightly at times that I thought I might bruise (I didn't). He also massaged my shoulders and back, my scalp, and even my forehead. I felt ridiculous getting my forehead massaged in the middle of a crowded teahouse, but the liberating thing about being a stranger in a strange land is that just about everything I do will seem odd, so why not?

On the way out of the park I admired a topiary structure of what appeared to be a dragon and a rooster going after a ball at the same time. A trio of pandas seemed to be in the works, but at the time they were just skeletons.

I biked back to the hostel without getting lost, and had about 20 minutes to spend online before taking the airport shuttle. While in China I mainly went online to triage my email and update my Facebook status lines.

An American named Josh was the only other person taking the shuttle from the hostel (we picked up one other person, a Chinese guy, on the way). It turned out we were on the same flight. We had other things in common too, like having been in China for about the same amount of time and having gone many of the same places there, being vegetarian, and having lived in DC, New York state, California, and the Southwest. But it was a long ride to the airport, and by the time we reached the departure lounge the conversation was flagging. Despite his very American friendliness there was something about Josh that annoyed me, perhaps a subtle sense of his own superiority, and I was ready to be alone again.

At baggage claim in Lijiang, Wangning and Henry asked if we'd like to share a taxi in from the airport, which we did, piling our backpacks in the middle seat of a van and exiling Josh to the front seat while the other three shared the back. Wangning is Chinese and Henry German; they met at college in Berlin. Wangning had been back for a year and was showing Henry around the country. I liked them.

The driver was unwilling to take Josh and I to our hotels in the Old Town, and so dropped us off at a taxi stand somewhere in Lijiang. Getting to the room I'd reserved at Mama's Naxi Guesthouse turned out to be no small feat. I'd been feeling very comfortable in China after my half-day of parks, tea, and massage, but was thoroughly tired, hungry, and grouchy by the time I found my lodgings. Even so I couldn't help but find the Old Town charming, with its narrow, carless cobbled streets, graceful buildings, and canals.

Next I called the cell phone for the Wenhai Ecolodge, a place I'd found a few months before when I Googled "Yunnan ecotourism." Going to an ecolodge in the jungle had been the highlight of my time in Peru, and I hoped there were similar opportunities in China. I'd made an email reservation with someone who seemed to speak English quite well, and now needed to work out how to get to the lodge. My options were hiking, horseback, or Jeep; I chose horseback. My pack was nice enough for jaunts around towns in search of hostels, but I'd never hiked with it, nor did I want to try. And having someone drive me up a mountain in a Jeep didn't seem very eco-friendly.

After taking care of a few other things I rented a bike and rode to what seemed to be Chengdu's main tourist shopping drag, a place with nice dark wood buildings. It adjoined a park where I went wandering, and confirmed my impression that going to the park is one of the best things to do in China. I saw an old man painting calligraphy on the paving stones with water and a giant brush. This in addition to the usual newspaper-reading, tea-drinking, and music-making.

I did have a destination in mind in the park, namely the Green Ram Taoist temple and its vegetarian restaurant. It's interesting how similar the Buddhist and Taoist temples look to my untrained eye. The main differences I picked out are the ubiquity of the yin/yang symbol (only Taoist), and the way the monks dress.

At the temples, I've seen monks chanting and people reverently lighting incense. I've also seen monks chatting on cell phones and hawking loogies, and woman kneeling to pray in a pink velour tracksuit with "Juicy" printed across her ass. It would be nice to get a tour of a temple sometime from someone knowledgeable, but until that happens, I'm not keen on going to more temples anytime soon.

At the restaurant, the waitress put a menu in front of me that looked like it might have been a relic of the Tang dynasty, if they'd had typewriters in the Tang dynasty. The edges of the pages were ragged. But I noticed later that the other patrons had nice menus with hard covers and laminated pages, and figured the waitress had given me the antique version because it was bilingual.

I was grateful for this, but it didn't completely solve my communication difficulties. When I pointed to a dish described as "pumpkin," the waitress tried to explain why I might not in fact want it, but I didn't understand. So she helpfully went and got the vegetable in question and showed it to me. I looked like an extremely warty cucumber. I nodded--I was in China to try new things, right?--but it turned out to be the most bitter vegetable I'd ever tasted. Fortunately I'd also ordered a tofu dish. I was beginning to catch on that even if you're a lone diner, and you know that Chinese portions are huge, you don't order just one thing at a Chinese restaurant.

Afterward I found my bike--this took a little time--and went to the People's Park in the heart of the city. This one has kiddie rides, full bands giving free concerts, and a garden of Bonsai trees. It also has a famous teahouse that I wanted to try. The teahouse is huge and sprawling, set on a small lake where families rent paddle boats. Men walk around tinging their ear-cleaning instruments (a sound much like a triangle) to advertise their services. I finally agreed to a 20-minute massage from one.

He focussed mostly on my arms, gripping them so tightly at times that I thought I might bruise (I didn't). He also massaged my shoulders and back, my scalp, and even my forehead. I felt ridiculous getting my forehead massaged in the middle of a crowded teahouse, but the liberating thing about being a stranger in a strange land is that just about everything I do will seem odd, so why not?

On the way out of the park I admired a topiary structure of what appeared to be a dragon and a rooster going after a ball at the same time. A trio of pandas seemed to be in the works, but at the time they were just skeletons.

I biked back to the hostel without getting lost, and had about 20 minutes to spend online before taking the airport shuttle. While in China I mainly went online to triage my email and update my Facebook status lines.

An American named Josh was the only other person taking the shuttle from the hostel (we picked up one other person, a Chinese guy, on the way). It turned out we were on the same flight. We had other things in common too, like having been in China for about the same amount of time and having gone many of the same places there, being vegetarian, and having lived in DC, New York state, California, and the Southwest. But it was a long ride to the airport, and by the time we reached the departure lounge the conversation was flagging. Despite his very American friendliness there was something about Josh that annoyed me, perhaps a subtle sense of his own superiority, and I was ready to be alone again.

At baggage claim in Lijiang, Wangning and Henry asked if we'd like to share a taxi in from the airport, which we did, piling our backpacks in the middle seat of a van and exiling Josh to the front seat while the other three shared the back. Wangning is Chinese and Henry German; they met at college in Berlin. Wangning had been back for a year and was showing Henry around the country. I liked them.

The driver was unwilling to take Josh and I to our hotels in the Old Town, and so dropped us off at a taxi stand somewhere in Lijiang. Getting to the room I'd reserved at Mama's Naxi Guesthouse turned out to be no small feat. I'd been feeling very comfortable in China after my half-day of parks, tea, and massage, but was thoroughly tired, hungry, and grouchy by the time I found my lodgings. Even so I couldn't help but find the Old Town charming, with its narrow, carless cobbled streets, graceful buildings, and canals.

Wenhai

I woke up early to the sounds of a cat crying insistently and of a German tourist telling the hostel worker her plans. Leaving my window open had been a mistake.

I gave up sleeping eventually, and showered and packed. The woman who worked there was no longer in the courtyard when I came out. No one had asked me for money the night before or even my passport, but no matter--Mama's Naxi Guesthouse was actually three guesthouses, and breakfast was served at a different one. I had a banana pancake there, actually a large piece of flat fried bread covered in sliced bananas, and paid for both the pancake and the room.

I was supposed to meet Cun Xuerong, the ecolodge manager, at 10:00 at a water wheel on the other side of the Old Town. My experience the night before had taught me that the Old Town is very difficult to navigate for the uninitiated, but miraculously, I arrived at 10:00 exactly. Mr. Cun, a handsome 30-something man with an urban air, found me quickly. He doesn't speak English, it turned out. I expressed surprise, since the emails from Wenhai had been signed with his name, but he said someone else had written them. The woman I'd talked to on the phone, surely.

We managed to communicate surprisingly well in Chinese, though. Perhaps Mr. Cun is used to talking to foreigners with a weak grasp of the language. Was I American? Yes. Was I working in China? I'd learned the word for "work" but forgotten it. I looked it up, then told him I didn't have a job in China, but was a tourist. Where had I studied Chinese, then? In college. Mr. Cun seemed pleasantly surprised to hear that colleges in America offer Chinese. He asked whether the instructors were Chinese or American. I said they were Chinese. It was by far the most successful conversation I'd had in Mandarin since arriving in the country.

Mr. Cun drove me in his Jeep to the foot of a mountain, where we waited for the guide and horse(s) to arrive. When I'd asked for the horse option I'd optimistically expected a guide on a horse, a horse for me, and perhaps a third animal for luggage, but now I worriedly watched a middle-aged man lead one small, dark, slightly mud-speckled horse out of the woods. Mr. Cun introduced me to Mr. He and told me to put my backpack on and mount the horse, which I did with some difficulty. The saddle was what I assumed to be the Naxi traditional style, unpadded with a hard loop of a handle in front.

I didn't particularly like being the tourist led along on a horse, but on our way up the mountain we saw Han tourists doing it too, and one middle-aged waiguoren couple. The path was steep, and the horse had to stop periodically to catch its breath. It wasn't long before my knees were stiff, my backside was sore, and I wished I were walking.

Mr. He is perhaps about 40, and small. He wore a battered sport coat, corduroys, and shoes resembling soccer cleats, plus a backpack with the vegetables Mr. Cun had bought for my meals. He didn't talk much.

We passed a dam, then a small reservoir. We crested the pass and soon afterward Mr. He suggested that I walk for the next stretch, which was particularly steep. I did so gladly, although my knees were so stiff I could barely walk at first. My dismount was no more graceful than my mount--I wasn't feeling like much of a martial artist.

Further down he had me get back on the horse, which moved away as I did. I joked that he didn't like me, but it wasn't really a joke.

As we neared the village we began to pass Naxi who weren't leading tourists on horses. Mr. He talked to all of them in a staccato language. We arrived at around 1:00, and Mrs. He cooked me lunch. It was simple and excellent: one plate of tomatoes and scrambled eggs, another of mushrooms and garlic, plus, of course, rice from a giant cooker.

But it soon began to seem to me that there was something off about the ecolodge. Mr. Cun had told me, when I asked him, that there were no other guests at the moment, and I hadn't expected luxury accommodations. but I had expected some sort of orientation. The Hes spoke no English, and the English-speaking woman I'd spoken to on the phone was nowhere in evidence. I'd have settled for a printout suggesting things to do, or even a patient explanation in Chinese and sign language, but it seemed that once I'd been shown my room and fed, I was on my own. Also, there was a distinct atmosphere of neglect: Huge cobwebs in the bathroom and hallways, plastic bottles piled under the stairs, and a receipt left in my room from the Grand Lijiang Hotel dating from early September.

Yet there was ample evidence that much care had gone into this place at one time. In the common room, where I ate, a sign announces that the lodge had been launched with funds from the Nature Conservancy and the Japanese government. The Nature Conservancy wanted to foster sustainable tourism in China to benefit the environment, and the Japanese wanted to show their friendship and help the people of Wenhai. Big framed posters, now dirty and faded, declaim in Chinese and flawless English on the philosophy of ecotourism, life in Wenhai, and regional flora and fauna. There are clipped articles on the lodge from the travel sections of the Daily Telegraph, the Far Eastern Economic Review, and the New York Times. These last two were both written in 2004 by the same freelancer, Craig Simmons. The articles sunnily describe the beauty of the setting, the difficulty of reaching the lodge, and its ecological amenities, which include solar panels, a biogas system, and a greenhouse. I wondered whether any of these were still working.

It was only 2:00, so I decided to do a little exploring. On my way out Mrs. He asked where I was going, and I answered truthfully that I didn't know. Perhaps I should have tried to provide more information.

I ambled around Wenhai Lake, which I'd learned is a seasonal lake, although I'm not quite clear on when it disappears. The only wildlife I spotted was a toad, but there were more free-roaming domestic animals than I'd ever seen before in one place: pigs, chickens, dogs, horses, cattle. I even saw some yaks, the first I'd ever seen outside of a zoo. The lake, the tiny streams that feed it, and the mountains--especially Jade Dragon Snow Mountain--made for some beautiful views. Time seem to melt away: Every time I looked at my watch, another hour had elapsed.

I got back to the ecolodge as it was growing dark, and Mrs. He served me three dishes this time, plus the ubiquitous tea (with a huge thermos for refills). As I was eating Mrs. He came in and handed me a cell phone. It was the English-speaking woman I'd talked to the day before. I don't know what she sounds like in Chinese or Naxi, but in English she comes across as strident.

"Hello? How are you?" with preliminaries out of the way, she asked me what I planned to do the next day. I said I didn't know. She told me I could walk around the lake and village by myself, but to go further afield I would need a guide. I didn't argue about that. She said that my options for the next day included climbing a mountain or walking to some Yi villages. Weighing this, I asked how far away the villages were. "Two are close, but two are farther away. But if you get tired you can just tell the guide, he'll take you home." I asked how difficult the climb up the mountain was. "If you get tired, I think you can tell Xiao He "hui jia," or you can speak to him in English, because he has guided many foreigners and I think maybe he understand you." This response seemed unecessarily patronizing--of course I could tell Mr. He "hui jia"--but if could communicate so well with the Hes, why was she calling me? I said I'd like to visit the Yi villages, and handed the phone back to Mrs. He.

The temperature dropped quickly after sundown, and the lodge was unheated, so I headed upstairs soon after dinner, taking the massive thermos with me. Next to my room was a door to the roof, and I went out. Here were the famous solar panels, or two of them anyway. One had a towel drying on it. On the wall were what appeared to be the panels' control or monitoring devices, but their digital displays were dark. Just to the side of the roof was a greenhouse I'd read about on an informative poster in the bathroom. In addition to nurturing vegetables, it was supposed to keep the biogas digester warm in winter so that it would keep working. But its clear plastic roof was almost entirely torn away, and the floor had been reclaimed by weeds.

I was sitting in bed reading about the Naxi in Lonely Planet when Mrs. He knocked at the door. I found her very difficult to understand. She asked whether I had a question or problem. I said no. She said something about the phone call. I tried to say yes, the woman on the phone and I talked about my going to the Yi villages tomorrow. She asked me something that I didn't understand. She said never mind, go back to sleep. Confused, I went back to bed.

I gave up sleeping eventually, and showered and packed. The woman who worked there was no longer in the courtyard when I came out. No one had asked me for money the night before or even my passport, but no matter--Mama's Naxi Guesthouse was actually three guesthouses, and breakfast was served at a different one. I had a banana pancake there, actually a large piece of flat fried bread covered in sliced bananas, and paid for both the pancake and the room.

I was supposed to meet Cun Xuerong, the ecolodge manager, at 10:00 at a water wheel on the other side of the Old Town. My experience the night before had taught me that the Old Town is very difficult to navigate for the uninitiated, but miraculously, I arrived at 10:00 exactly. Mr. Cun, a handsome 30-something man with an urban air, found me quickly. He doesn't speak English, it turned out. I expressed surprise, since the emails from Wenhai had been signed with his name, but he said someone else had written them. The woman I'd talked to on the phone, surely.

We managed to communicate surprisingly well in Chinese, though. Perhaps Mr. Cun is used to talking to foreigners with a weak grasp of the language. Was I American? Yes. Was I working in China? I'd learned the word for "work" but forgotten it. I looked it up, then told him I didn't have a job in China, but was a tourist. Where had I studied Chinese, then? In college. Mr. Cun seemed pleasantly surprised to hear that colleges in America offer Chinese. He asked whether the instructors were Chinese or American. I said they were Chinese. It was by far the most successful conversation I'd had in Mandarin since arriving in the country.

Mr. Cun drove me in his Jeep to the foot of a mountain, where we waited for the guide and horse(s) to arrive. When I'd asked for the horse option I'd optimistically expected a guide on a horse, a horse for me, and perhaps a third animal for luggage, but now I worriedly watched a middle-aged man lead one small, dark, slightly mud-speckled horse out of the woods. Mr. Cun introduced me to Mr. He and told me to put my backpack on and mount the horse, which I did with some difficulty. The saddle was what I assumed to be the Naxi traditional style, unpadded with a hard loop of a handle in front.

I didn't particularly like being the tourist led along on a horse, but on our way up the mountain we saw Han tourists doing it too, and one middle-aged waiguoren couple. The path was steep, and the horse had to stop periodically to catch its breath. It wasn't long before my knees were stiff, my backside was sore, and I wished I were walking.

Mr. He is perhaps about 40, and small. He wore a battered sport coat, corduroys, and shoes resembling soccer cleats, plus a backpack with the vegetables Mr. Cun had bought for my meals. He didn't talk much.

We passed a dam, then a small reservoir. We crested the pass and soon afterward Mr. He suggested that I walk for the next stretch, which was particularly steep. I did so gladly, although my knees were so stiff I could barely walk at first. My dismount was no more graceful than my mount--I wasn't feeling like much of a martial artist.

Further down he had me get back on the horse, which moved away as I did. I joked that he didn't like me, but it wasn't really a joke.

As we neared the village we began to pass Naxi who weren't leading tourists on horses. Mr. He talked to all of them in a staccato language. We arrived at around 1:00, and Mrs. He cooked me lunch. It was simple and excellent: one plate of tomatoes and scrambled eggs, another of mushrooms and garlic, plus, of course, rice from a giant cooker.

But it soon began to seem to me that there was something off about the ecolodge. Mr. Cun had told me, when I asked him, that there were no other guests at the moment, and I hadn't expected luxury accommodations. but I had expected some sort of orientation. The Hes spoke no English, and the English-speaking woman I'd spoken to on the phone was nowhere in evidence. I'd have settled for a printout suggesting things to do, or even a patient explanation in Chinese and sign language, but it seemed that once I'd been shown my room and fed, I was on my own. Also, there was a distinct atmosphere of neglect: Huge cobwebs in the bathroom and hallways, plastic bottles piled under the stairs, and a receipt left in my room from the Grand Lijiang Hotel dating from early September.

Yet there was ample evidence that much care had gone into this place at one time. In the common room, where I ate, a sign announces that the lodge had been launched with funds from the Nature Conservancy and the Japanese government. The Nature Conservancy wanted to foster sustainable tourism in China to benefit the environment, and the Japanese wanted to show their friendship and help the people of Wenhai. Big framed posters, now dirty and faded, declaim in Chinese and flawless English on the philosophy of ecotourism, life in Wenhai, and regional flora and fauna. There are clipped articles on the lodge from the travel sections of the Daily Telegraph, the Far Eastern Economic Review, and the New York Times. These last two were both written in 2004 by the same freelancer, Craig Simmons. The articles sunnily describe the beauty of the setting, the difficulty of reaching the lodge, and its ecological amenities, which include solar panels, a biogas system, and a greenhouse. I wondered whether any of these were still working.

It was only 2:00, so I decided to do a little exploring. On my way out Mrs. He asked where I was going, and I answered truthfully that I didn't know. Perhaps I should have tried to provide more information.

I ambled around Wenhai Lake, which I'd learned is a seasonal lake, although I'm not quite clear on when it disappears. The only wildlife I spotted was a toad, but there were more free-roaming domestic animals than I'd ever seen before in one place: pigs, chickens, dogs, horses, cattle. I even saw some yaks, the first I'd ever seen outside of a zoo. The lake, the tiny streams that feed it, and the mountains--especially Jade Dragon Snow Mountain--made for some beautiful views. Time seem to melt away: Every time I looked at my watch, another hour had elapsed.

I got back to the ecolodge as it was growing dark, and Mrs. He served me three dishes this time, plus the ubiquitous tea (with a huge thermos for refills). As I was eating Mrs. He came in and handed me a cell phone. It was the English-speaking woman I'd talked to the day before. I don't know what she sounds like in Chinese or Naxi, but in English she comes across as strident.

"Hello? How are you?" with preliminaries out of the way, she asked me what I planned to do the next day. I said I didn't know. She told me I could walk around the lake and village by myself, but to go further afield I would need a guide. I didn't argue about that. She said that my options for the next day included climbing a mountain or walking to some Yi villages. Weighing this, I asked how far away the villages were. "Two are close, but two are farther away. But if you get tired you can just tell the guide, he'll take you home." I asked how difficult the climb up the mountain was. "If you get tired, I think you can tell Xiao He "hui jia," or you can speak to him in English, because he has guided many foreigners and I think maybe he understand you." This response seemed unecessarily patronizing--of course I could tell Mr. He "hui jia"--but if could communicate so well with the Hes, why was she calling me? I said I'd like to visit the Yi villages, and handed the phone back to Mrs. He.

The temperature dropped quickly after sundown, and the lodge was unheated, so I headed upstairs soon after dinner, taking the massive thermos with me. Next to my room was a door to the roof, and I went out. Here were the famous solar panels, or two of them anyway. One had a towel drying on it. On the wall were what appeared to be the panels' control or monitoring devices, but their digital displays were dark. Just to the side of the roof was a greenhouse I'd read about on an informative poster in the bathroom. In addition to nurturing vegetables, it was supposed to keep the biogas digester warm in winter so that it would keep working. But its clear plastic roof was almost entirely torn away, and the floor had been reclaimed by weeds.

I was sitting in bed reading about the Naxi in Lonely Planet when Mrs. He knocked at the door. I found her very difficult to understand. She asked whether I had a question or problem. I said no. She said something about the phone call. I tried to say yes, the woman on the phone and I talked about my going to the Yi villages tomorrow. She asked me something that I didn't understand. She said never mind, go back to sleep. Confused, I went back to bed.

Thursday, January 01, 2009

Forbidden fruit

I woke up late and went down to take a shower in the cobwebbed bathroom that Simmons described as "shared but clean" (it was neither shared nor particularly clean at the moment). There was no hot water, where depressed me. Not because I couldn't shower, which didn't seem too important in a place this remote, but because the water was supposed to be heated by the solar panels. I stood shivering in the concrete bathroom, with its bilingual posters on sustainability, and decided there was no way I could stay there for the three nights I'd reserved.

At breakfast I asked Mr. He for the cell phone, and told the English-speaking woman I'd like to leave the next day. She didn't ask why or seem disappointed, just asked how I'd like to get down the mountain. I said I'd like to walk but have the horse carry my bag. She said sure, and would I like to go the same way or take a different route down the mountain? I chose the latter.

Mr. He and I set off after breakfast (dumplings and shredded potatoes). I'd thought there were no shops at all in Wenhai, but on the way out of the village Mr. He bought something at a window in a cinder block building. Certainly people find a way to buy things there, judging by the snack wrappers and beverage containers that litter the paths. Probably there isn't much of a trash-disposal system there.

We passed through one tiny Yi village where no one was about. Before we even saw the second village I heard gun reports periodically, which echoed from the other side of the valley like soft thunder. Closer in I thought I heard firecrackers, too. But it was the middle of the day.

As we got closer still I saw a large group of people gathered on a path above the village. The shots were being fired into the air from a field next to them. There was cheering and laughter. Further up the hillside a yak was tied to a tree.

I asked Mr. He what was going on, and he said it was a "si le." This wasn't in my dictionary, but I assumed it meant a wedding. He pointed to the yak and drew the blade of his hand across his neck to indicate it would be killed.